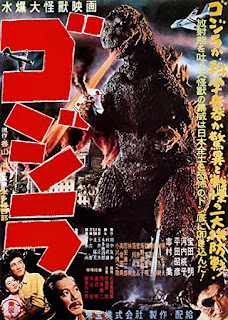

Oh no, there goes Tokyo.

As I write this, we’re getting the sequel to the 2014 reboot

of Godzilla, King of the Monsters, with promises of kaiju action cranked up to

eleven on the batshit insanity meter. The current decade certainly seems to

have seen a resurgence of the giant monster genre, going back to Cloverfield

and then of course to Pacific Rim, with projects like Rampage in the middle.

But for now, let’s forget all of that—let’s also forget the first time Hollywood

tried to do its own spin on this series. And let’s forget most of the original

series for that matter, as I want to take you back to 1954, and focus entirely

on this one little flick by Ishiro Honda called Gojira, to give my thoughts on

it.

Let’s set the scene—sixty-five years ago, Japan was not even

a decade out of the ravages of the Second World War, with the atomic specter

looming over both it and the United States. America took a more enthusiastic

and fantastical approach to the nuclear age—let’s have giant ants ravaging

California that our brave boys have to eradicate with flamethrowers! Atom-powered

batteries in our cars by the far future of 1985! Brush your teeth with radium

for a healthy glow!

The Japanese, however, still reeled from not only the

firebombing of Tokyo, but Hiroshima and Nagasaki being flattened by the most

devastating weapons yet conceived by man. Toho Studios decided to do their own

take on the sort of atomic-born monster films the US was making, like The Beast

from 20,000 Fathoms, but the tone was very different. Not only were they drawing

from the still recent memory of mushroom clouds, but of the continuing effects

of atomic testing and Cold war escalation. One of these was the ‘Lucky Dragon’

incident, in which a fishing boat drifting too close to an American test found

its catch irradiated, sparking panic in Japanese fish markets. These fears,

these traumatized recollections, turned what could’ve been a knockoff B-movie

into something very serious and special.

Godzilla, or Gojira, whichever you prefer, doesn’t hold back

on this either—starting right off the bat with a fishing boat caught in a

nuclear blast, directly referencing the Lucky Dragon. You don’t have to be

familiar with Japan’s zeitgeist at the time to get a sense of immediate

escalating threat, as subsequent vessels are also lost to things mysterious.

It’s fairly briskly paced too, introducing the main characters of Ogata and

Emiko (played by Akira Takarada and Momoko Kochi), a salvage ship operator and

daughter of the scientist investigating these incidents respectively. There’s

some clichés of the time like spinning newspapers and people talking into

radios very fast, but it’s still pretty watchable to modern viewers.

Before long, we find ourselves on a remote island, with some

neat glimpses of old Japanese customs that ties the film into ancient

mythologies that give it just a little more gravitas. Godzilla’s first attack

happens here, technically, and like any good horror movie, it’s shot and

directed just right to keep your imagination going just a bit more—you only

catch a glimpse of houses caving in during a storm, and something moving in the

night. Even so, the film doesn’t wait too long before we finally see the

titular kaiju, looking over a hill, and for the time, it’s quite a shot.

I compare some of this to horror movies, and honestly, for a

lot of it, it’s fairly apt. Godzilla tends to be seen at night for the most

part, silhouetted, with sometimes just his eyes visible as pinpricks, making

him look positively demonic at times. Considering the limitations of budget and

technology Toho had, its really very well done, and still genuinely

spine-chilling in cinematography throughout. Some little details enhance it in

all the right ways—the real reason Godzilla has that bumpy skin texture? That’s

because here, he’s meant to be covered from head to toe in keloid scars, just

like real fallout victims of the Japanese atomic bombings. Now isn’t that a

thought to bear in mind even for those that chuckle at rubber suits.

|

| Damn. |

Aside from the horror aspect, the film doesn’t shy away from

the tragic elements—even Godzilla is given sympathy, as just a creature forced

out of his habitat by nuclear tests, scarred and provoked, and further

disturbed by naval attacks and spotlights cast at him. The human emotional side

is certainly not shied away from—Emiko’s father, Doctor Yamane, is constantly

agonizing about whether to kill such a unique creature, and that’s before we

get introduced to Akihiko Hirata’s Doctor Serizawa. Serizawa arguably

represents the generation of Japanese that survived the war, barely, and is wrought

with bitterness and cynicism. His response to new technologies, that created

and could defeat Godzilla, is disgust and regret, and Hirata really lets these

feelings loose in his performance at times.

Some might consider the first act a little dull, with lots

of meetings and dated scientific jargon (dinosaurs are only two million years

old, apparently), but things really kick in with Godzilla’s first attack, at

the Tokyo docks. The miniatures still look really good for the time, and

Godzilla himself is shot just right, with lots of low angles, fog, and contrast

to enhance the atmosphere. Though there are the occasional model shots current

audiences might scoff at (later on, there’s a skidding toy fire truck that even

for the time looks hokey), it’s the seriousness with which the actors take it,

combined with the presentation that combines horror and disaster, that still

gives it effectiveness.

And then there’s Godzilla’s second attack. This is truly the

highlight of the film, by god, this remains one of the best monster rampages

even sixty five years later. There’s no encouragement to the audience to find

any of it cool or arsum, there’s no loving shots of demolition dominos—as

befitting something made for and by those that saw the destructive aerial

campaigns of total war, it’s shot as a horrific nightmare unfolding. People are

seen crushed by falling debris, the skyline burns apocalyptically, and we even

see a weeping mother tell her children ‘we’ll be seeing daddy soon’ before she

perishes. The black and white arguably enhances the visuals amazingly, giving

it that nightmare feel. And considering all the pyrotechnics, you really have

to give props to the man in the suit, Haruo Nakajima, who is still celebrated

in Japan, even down to their coffee ads.

|

| Daaaaaamn. |

If all that imagery wasn’t enough, we’re shown the aftermath

of the attack, with Tokyo smouldering, hospitals crammed, and children

diagnosed with radiation poisoning. There’s even a choir of schoolgirls extolling

for peace. Jaded viewers might scoff at the monster suits and miniature

vehicles, but this part? I challenge people not to watch it with a sober face,

considering the historical pretext looming over it all.

Eventually, Serizawa and the others agonize over using a weapon

that could kill the monster, but might only add to the arms race. Eventually,

the doctor sacrifices himself and destroys his research, with Godzilla defeated

seemingly for good. The film ends on a very bittersweet note as such, with the

characters wondering where mankind’s appetite for destruction could go next.

The 1954 original is often seen as the best of the series;

maybe some of the effects are primitive, maybe some aspects are rooted in the

time, but it has a sincerity and an uncompromised message that goes together with

an apocalyptic, doomy atmosphere. You may need to go into it with that

historical mindset to appreciate it fully, but still, I can easily argue why

it’s a well made flick of its time. It certainly resonated with Japanese

audiences of the time, and made lots of money. And with money, comes studio

executives wanting more!

A sequel came out very soon, called Godzilla Raids Again,

having him fight another monster for the first time. This has much more of the

rubber suit cheesiness the series would become known for, with much less of the

great cinematography and lighting, and more odd uncranking. Still, the original

was imported to the US around the same time, given an American recut with

Raymond Burr as an American reporter commenting on absolutely everything

spliced in (and some of the anti-nuclear pessimisms toned down, because hey,

gotta have that radioactive toilet seats!).

A decade later into the sixties, and the series came back with

the famous monster mash of King Kong vs Godzilla. Entertaining, but silly, and

the films kept going this way, increasingly aimed at kids with Godzilla himself

looking more and more like the cookie monster. From this period, I recommend

such glorious nonsense as Godzilla vs Megalon, which has silly kaiju fights

worthy of WWF, or whatever the hell Godzilla vs the Smog Monster is about.

|

| Er...damn? |

In

time, though, the series would return to its serious roots when bought back in

the eighties. Films I’ve seen from around then include Godzilla vs Destoroyah,

a direct sequel to the original on its 40th anniversary, which has

such metal things as a burning Godzilla in meltdown fight a demonic precambrian

crustacean.

Through all of the decades, the serious has had ups and downs,

being serious or silly, surprisingly well made or half-assed schlock. I’ve

talked about the 1998 Roland Emmerich version, which was middling even for

these sorts of films; and while the 2014 Gareth Edwards attempt may

understandably not have completely resonated with audiences spoiled by

extravaganzas like Pacific Rim, I at least appreciate the effort to recreate

some of the atmosphere and mood of the Ishiro Honda original. Sure, the 1954

film may have been made in that window where you could get away with being

utterly dead serious about radioactive lizards, but that’s what makes it all

the more special.

Toho went on to do their own reboot in 2016 with Shin

Godzilla, bringing on the director of seminal anime series Neon Genesis

Evangelion. This one wasn’t perfect, but definitely distinct—as the original

touched on the memory of the atomic bombings, this one touched on disasters

like Fukushima, and had an overtone of satire that savaged the Japanese

government. Godzilla himself, for the first time in years, was presented as a

creature malformed by nuclear excess, in constant pain and constant mutation.

Some people might find chunks of it dull, but it the rest was definitely

memorable, with one or two segments best described as ‘absolutely nuts’. So if

you weren’t keen on the 2014 version, you’ll at least find lots to discuss with

this one.

|

| Okay, daaamn. |

Some might find the original film just a curiosity, but it’s

a curiosity with significance and one that if nothing else gives a good reading

of the mood in that part of history. Dozens of films, a couple of mediocre

animes, and multiple reboots later, it remains one of the best fifties science

fiction flicks, and one I can still enjoy coming back to.

What else is there to say, besides—go go Godzilla.

Comments

Post a Comment