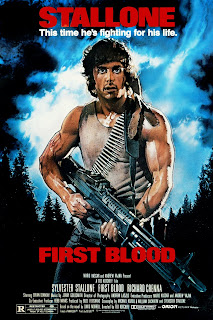

1982 was an interesting year in cinema—from Sophie’s Choice to Blade Runner, from Fitzcarraldo to ET, there’s quite a few classics across genres and audiences I can think of, most of which have stood the test of time just fine. We’ll be taking a look at several of them over time—but first up comes the first, and largely considered the best, of the Rambo series. It’s a film about a mentally scarred man lashing out against the nation that cast him aside, pushed to the brink by prejudices and his own trauma…what, you weren’t confusing this with the sequels, were you?

It’s true that Sylvester Stallone’s work can be outright meatheaded, or powerfully sincere, or sometimes both. The original Rocky was an honest reflection of his years struggling in lower-class areas, desperately reaching merely for the opportunity to go the distance, for instance…and then we get to the silliness of the sequels. You’ve got nonsense like Cobra, but then you’ve got rather biting commentary in Demolition Man—and that’s why Sly’s filmography, with all its ups and downs, leaves a lot to talk about if nothing else. That definitely goes for First Blood here—which for me contains one of the most hitting moments of his career, as we’ll get to.

The story starts off straightforward enough—homeless Vietnam veteran John Rambo wanders into a small town in search of a comrade now dead from Agent Orange exposure (hm, I have bought up Vietnam-related films a fair bit lately, haven’t I? Well it’s not like nations, not only the US, really learned that much from it…). With one more anchor for him gone, he gets on the bad side of the bigoted local sheriff (Brian Dennehy) almost immediately. Both their stubbornness soon escalates into arrest, then breakout, then the accidental death of a police officer—and things only escalate from there as a low-level guerrilla war between Rambo and the authorities ensues.

It’s sometimes mentioned that the film is based on a novel by David Morrell, where things are somewhat more morally ambiguous, and the sheriff’s character more fleshed out. While you certainly get glimmers of his motivation and background in the film, and more in the deleted scenes, there was certainly room for a little bit more—then again, some might argue, it hardly seems unrealistic now for a law enforcement officer like that to be unpleasant to anyone who looks at him funny just ‘cause. Either way, at least, Sheriff Teasle certainly feels more down-to-earth than the cartoon bad guys we’d get in future instalments and their imitators, and the film does at least adequately portray just why he steadfastly refuses to give up his vendetta against Rambo.

Despite the series’ reputation, there’s not a lot of full-on action as we’d think of it—Rambo’s modus operandi is to create traps in the forest, and strike from camouflage—when cornered by heavily armed National Guardsmen, he essentially slips away by luck then just mowing them down. It’s that element of realism that makes those moments where he flashes back to his torment in Vietnam actually have any weight—which, as we’ll get to, is that critical element to the film still managing to have resonance.

Another highlight is Richard Crenna as Rambo’s mentor Colonel Trautman—whose character has been referenced, parodied, and homaged across all sorts of media. Even though he comes in around the last act, it’s Crenna’s absolute steadfast delivery that sells otherwise slightly overblown lines, and it’s not hard to see why he returned for nearly all of the sequels.

But that gets us only to the last scene—where Rambo is cornered, surrounded by hundreds of armed men, and finally confronted by Trautman. At this point, Stallone cuts loose, and our protagonist completely crumbles, succumbing finally to the trauma that his little war has bought to the forefront. Sure, Sly’s slurring makes it a little hard to follow—but that hardly matters when he’s visibly pouring his heart out. It’s ironically a perfect deconstruction of the action hero archetype we’d see through the decade to come and through many of his own films—past the bravado, badassrey, and talent, John Rambo is exposed as a husk of a man who essentially already died in Vietnam. Much like all the many recorded cases of broken soldiers crying out for mommy and daddy, he’s reduced to a sobbing wreck before the closest thing he has to a father figure. The ending initially filmed was even more of a brutal gut-punch—there, Rambo finally decides to end his war, and turns his weapon in on himself.

It’s something that was arguably necessary in film—prior to this, PTSD-wounded Vietnam veterans were often depicted as dangerous or at best unstable, with the more sympathetic version here being the first major portrayal I can think of to start moving beyond that. Ill-conceived as the war may have been, brutal some of its participants on the US may have been, that doesn’t change that many were young men tossed into something they barely understood, to return broken with little in the way of options for help. There were certainly many John Rambos who simply faded away on the street, put out of sight and out of mind when no longer of use.

Of course, then came the sequels, and, well, time for Rambo to return to Vietnam to mow down more NVA and get captured all over again, because I guess PTSD has diminishing returns apparently! First Blood Part 2 may have had its part in catharsis in the Reagan years, but honestly, for enjoyably silly meathead action films from 1985, I’d stick with Schwarzenegger’s Commando. And we can of course talk about the ironic-on-multiple-levels nature of Rambo 3 with it’s Afghanistan setting…

Either way, First Blood still certainly has its part in the zeitgeist in both cinema and culture—some parts may seem a little on the nose now but the overall message and theme remains on point. In conflicts since, we still have veterans struggling on return to their home societies—ignored by certain political bodies that claim to all about supporting them. Like I said, in many ways, little has been over the last half-century—and even now, those issues remain hovering thicker as they ever were. As Stallone himself puts it in this one, nothing is over…

Comments

Post a Comment